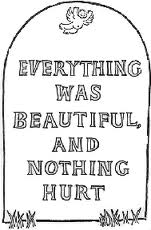

Kurt Vonnegut was a twentieth century American writer, playwright, and artist most known for his novels critiquing war, religion, government, and group think within society. His most notable works include Slaughterhouse-5, Cat’s Cradle, and Mother Night. Vonnegut was also the president of the American Humanist Association from . Humanism is a philosophy that focus on the deriving morals and values from human origins as opposed to the divine. Or as Vonnegut himself put it, “‘I am a humanist, which means, in part, that I have tried to behaved decently without expectations of rewards or punishments after I am dead” (Friedman).

Vonnegut was born during the early part of the twentieth century to working-class parents in Indianapolis, Indiana. Vonnegut suffered great losses during his childhood, “Vonnegut's father fell into severe depression and his mother died after overdosing on sleeping pills the night before Mother's Day. This attainment and loss of the ‘American Dream’ would become the theme of many of Vonnegut's writings" (Vonnegut Bio). During World War II he was a prisoner of war after the Battle of the Bulge, and during his imprisonment witnessed the firebombing of Dresden, Germany. The firebombing was an allied forces bombing raid that kill more people and did more damage than either of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. This incident servers as a primary story-line in his great anti-war book Slaughterhouse-5.

Later in life Vonnegut used these experiences as the basis for many of his stories. Throughout his life Vonnegut has been critical of military action and many of his books deal with the nature of technology in opposition to human morality. Kurt Vonnegut died in April of 2007.

Long Walk to Forever

Kurt Vonnegut

Monday, May 9, 2011

The Bokononist Religion

The novel Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut contains within it Vonnegut's critique of religion. The vehicle used for this purpose is the made up religion known as Bokononism. Bokononism is found by the character “Lionel Boyd Johnson” who, in the language of the fictional citizen of the island nation of San Lorenzo, is known as Bokonon. Bokonon and the character “Corporal Earl McCabe” put themselves in charge of San Lorenzo, without a complaint by any of the inhabitants (122). The goal of the two was to create a Utopian Paradise, and as a result, created a new religion for the island nation. A Calypso of Bokonon explains as such:

I wanted all things

To seem to make some sense,

So we all could be happy, yes,

Instead of tense.

And I made up lies

So that they all fit nice,

And I made this sad world

A par-a-dise.

Through a series of Calypso's and quotes from the holy Book of Bokonon, Vonnegut expresses his view on the purpose of religion and how religions attain power. Vonnegut presents the idea that religions are useful because the bind people together for a common purpose, regardless of blood relation, political affiliation, or other such groups. The view is that God provides a group of people with a network of other individuals in a grand design that is above the minds of those in, as he names it, the karass. Bokonon's fifty third Calypso presents this idea:

Oh, a sleeping drunkard

Up in Central Park,

And a lion-hunter

In the jungle dark,

And a Chinese dentist,

And a British queen--

All fit together

In the same machine.

Nice, nice, very nice;

Nice, nice, very nice;

Nice, nice, very nice--

So many different people

In the same device.

In the same device.

- The final bit of advice that Vonnegut gives through the prism of Bokonon is contained within the very short book with a long title, the fourteenth book of Bokonon, which reads as such:

Nothing.

- 'Nothing' is the only word in the fourteenth book. A primary point in Cat's Cradle is the fact that the religion is fake, with the hint that all religions are fake and their use is to comfort and give hope to people, not to give the truth.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Vonnegut the Artist

Kurt Vonnegut the artist.

Kurt Vonnegut is predominately known as a writer of short stories and science fiction. Less well known is his artistic side. His medium of choice is drawings. His first published works were within his novel Breakfast of Champions (Vonnegut.com). His artwork is whimsical and straightforward much like his own writing. Breakfast of Champions is a gimicky book in the sense that the drawings plan an important role within the book; the narrator refers to them constantly.

Later in his career, Vonnegut turned his artistic focus towards painting, and in 1983 held a one man show in New York displaying his works. The focus on painting is a result of the apparent difficulty that writing presents, in his words he states "writing is labor, and the writer's reward arrives when he or she hands the manuscript to the editor and says, 'It's yours.' The painter gets his rocks off while actually doing the painting. The act itself is agreeable' (Interview with Peter Reed).

Kurt Vonnegut is predominately known as a writer of short stories and science fiction. Less well known is his artistic side. His medium of choice is drawings. His first published works were within his novel Breakfast of Champions (Vonnegut.com). His artwork is whimsical and straightforward much like his own writing. Breakfast of Champions is a gimicky book in the sense that the drawings plan an important role within the book; the narrator refers to them constantly.

Later in his career, Vonnegut turned his artistic focus towards painting, and in 1983 held a one man show in New York displaying his works. The focus on painting is a result of the apparent difficulty that writing presents, in his words he states "writing is labor, and the writer's reward arrives when he or she hands the manuscript to the editor and says, 'It's yours.' The painter gets his rocks off while actually doing the painting. The act itself is agreeable' (Interview with Peter Reed).

Monday, May 2, 2011

Vonnegut the Humanist

Showing his skepticism, Vonnegut even warns of putting too much faith in science and treating it as a new God; again from his acceptance speech, "So science is yet another human made God to which I, unless in a satirical mood, an ironical mood, a lampooning mood, need not genuflect" (Vonnegut). He explains in his speech how when he was younger he was relieved to note that devices of torture, like thumb screws and iron maidens, were not in use anymore. Later, after a lifetime worth of seeing war, from his own service in World War II, to the Korean War, Vietnam, and subsequent military action, he notes "the horrors of those torture chambers--their powers of persuasion--have been upgraded, like those of warfare, by applied science, by the domestication of electricity and the detailed understanding of the human nervous system, and so on" (Vonnegut). Science, while it has no morality, should be influenced by a desire to provide goodness in the world. Instead of finding a God in science, it seems as if we've created a Devil.

Vonnegut and Long Walk to Forever

“Long Walk to Forever” By Kurt Vonnegut presents a situation in which a man and a woman who grew up together reconnect a week before her wedding to another man. The plot is well-trod ground, boy is childhood friend of girl, boy leaves for X reason and girl meets boy 2. The first boy returns from X and find girl and convinces her to be with him. This plot is standard romantic-comedy fare, such as in the movies The Notebook, Great Expectations, and When Harry Met Sally, only to be out done by the Girl detests Boy and then falls for Boy trope. In “Long Walk to Forever” the characters “Newt” and “Catherine” share a mutual attraction but never act on it. Newt joins the Military while Catherine meets and becomes engaged to “Henry” . Newt returns and Catherine is at first frustrated by Newt because prior to leaving for the Military he never told her how he felt. As the story goes, we learn that Henry is a nice man, but Catherine has that “something” with Newt. As with the majority of stories like this Catherine ends up with Newt.

Kurt Vonnegut is most known for his science-fiction works such as Slaughterhouse-5, Cat’s Cradle and Harrison Bergeron. “Long Walk to Forever” is a purely character driven story without a hint of focus on technology. Pure and simple, this is a story about a boy, a girl and love. Most of his popular works have some element of fantastical science, such as the Ice-9 from Cat’s Cradle or the character “Billy Pilgrim” from Slaughterhouse-5 and his subsequent time-traveling. The New York Times Book reviewer David Eggers explains the disconnect; “Vonnegut was until early middle age a practical and adaptable writer, a guy who knew how to survive on his fiction. In the era of the “slicks” — weekly and monthly magazines that would pay decently for fiction — a writer had to have a feel for what would sell” (Eggers para 4). Many of the stories in Welcome To The Monkey House share this medium and the book is actually a compilation of previously published stories from various magazines.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)